So-called ‘ridesharing’

Bezzle

Fig. 1. “Clarkdale Classic Gas Station, Clarkdale, Arizona,” Photograph by Alan Levine, October 28, 2016, via Wikimedia Commons, CC0.

Preetika Rana, “Lyft Shares Slide After Disappointing Revenue and Ridership Numbers,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/lyft-q3-earnings-report-2022-11667852844

Ashley Capoot, “Uber beats estimates and the stock is up,” CNBC, February 8, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/08/uber-earnings-q4-2022.html

Levi Sumagaysay, “Lyft stock sinks 30% after sales outlook falls short of $1 billion,” MarketWatch, February 9, 2023, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/lyft-stock-sinks-more-than-20-after-sales-outlook-fails-to-reach-1-billion-11675977504

Laura Forman, “Lyft’s Defensive Driving Stalls Out,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/lyfts-defensive-driving-stalls-out-2efc5f99

Drivers

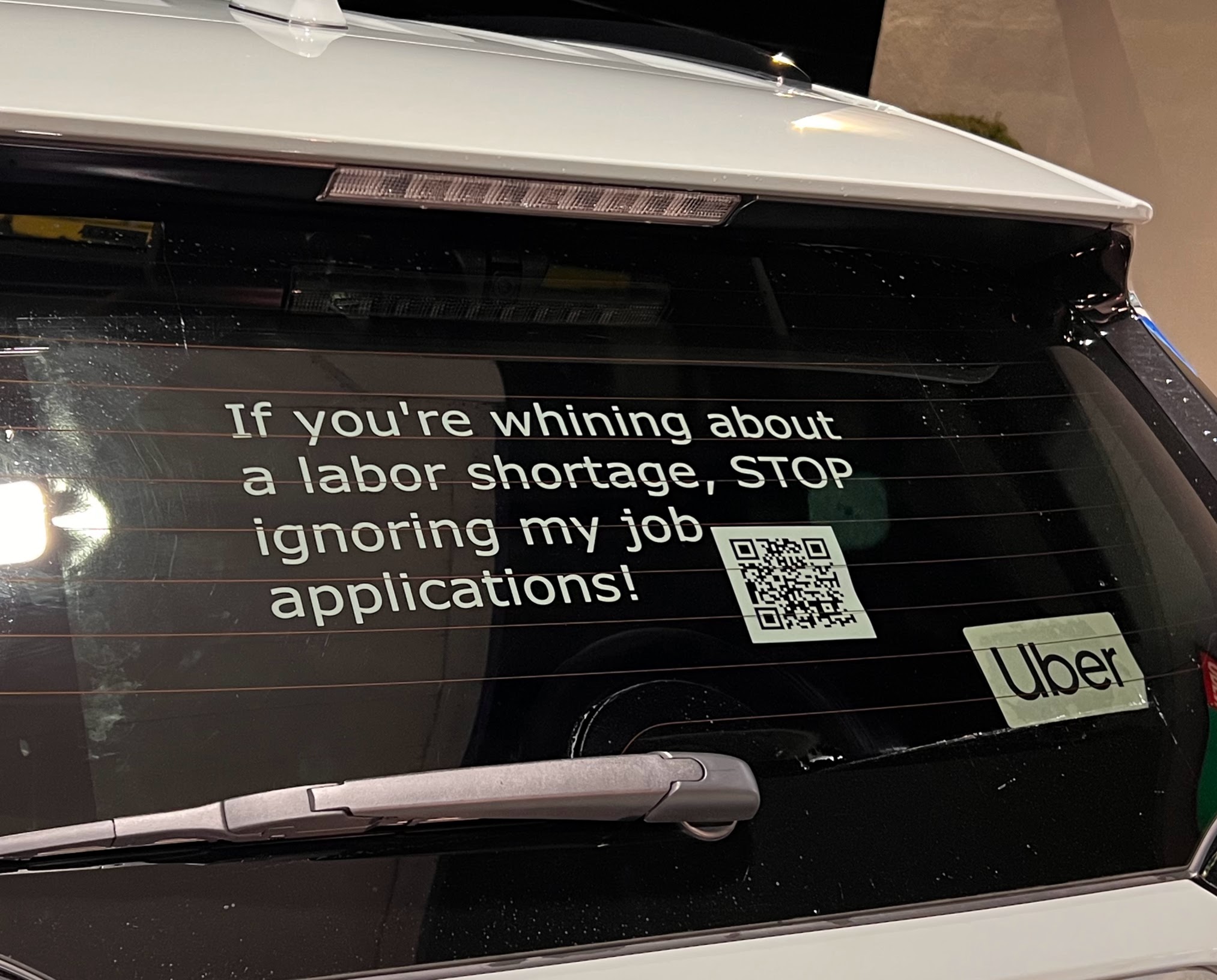

Fig. 2. Yeah, this is me. The sign says, “If you’re whining about a labor shortage, STOP ignoring my job applications!” And the QR-code leads here. Photograph by author, January 16, 2023.

Uber and Lyft compete to exploit and abuse the desperate and the stupid. I realize that makes them think they are good capitalists. But the worst imagery of Hell would be of far too kind a place.

I’ve been doing as deep a dive as I’m able to of my numbers and I’ve come up with a chart (figure 3) that illustrates the combination of precarity and uncertainty that I assume is somewhat typical of so-called “rideshare” driving.

Fig. 3. Graph of estimated daily average net income (in blue, using Internal Revenue Service mileage allowance) by month since January 2022, what the federal minimum wage would be for a six-and-a-half hour day had it kept pace with productivity[1] (in orange), and the federal poverty line[2] (in red), created by author, February 10, 2023.

The first thing to notice is that, in terms of a livable income, the numbers are low, well below what the minimum wage would be had it kept pace with productivity ($23 per hour),[3] and recently pretty close to the official U.S. federal poverty line ($13,590 per year, or $1,132.50 per month in 2022) for an individual[4] (an outdated measure[5]). In December 2022, I actually fell below that line. This is precarity and it’s why I’ve been driving seven days a week.

I don’t keep track of my time, but I generally drive six or seven hours per day, which is about as much of Pittsburgh driving as I can stand.[6] I avoid the drunks (no, I don’t want people vomiting in my car) as much as possible and times when people are more likely to be shooting at each other. In practice, this means I am usually out by around noon and cutting off orders by around 6:30 pm. This also gives me time to get to a car wash before they close at 7:00 pm or 8:00 pm.

The second thing is the extreme variation (as of February 9, 2023, the standard deviation is $26.11 against an average of $67.62) from month to month. This is unpredictability.

What’s happening here is that Uber and Lyft offload business risk onto people who can’t afford it, misclassifies them as “independent contractors,” and denies them the protections, benefits, and minimum wage that employees are entitled to. Meanwhile, both companies claim to be investing in attracting drivers,[7] but it is clear that their results come very much at drivers’ expense, particularly as Uber claims to have gained drivers as a consequence of inflation,[8] and then pays them next to nothing. That’s exploitation.

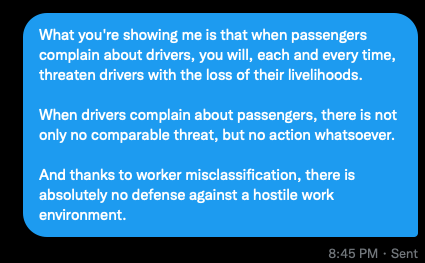

Fig. 4. Screenshot of direct message sent to Uber Support by author, December 15, 2022.

When finally we consider the discrepancy in how the companies treat drivers and passengers when one complains against the other, with drivers’ livelihoods routinely threatened but nothing at all, as near as I can tell, done to passengers (figure 4), we see abuse.

If you have any intelligence at all, you will not voluntarily drive for these companies. I do so only because I am desperate.[9]

- [1]Dean Baker, “Correction: The $23 an Hour Minimum Wage,” Center for Economic Policy and Research, March 16, 2022, https://cepr.net/the-26-an-hour-minimum-wage/↩

- [2]U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Federal poverty level (FPL),” n.d., https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/↩

- [3]Dean Baker, “Correction: The $23 an Hour Minimum Wage,” Center for Economic Policy and Research, March 16, 2022, https://cepr.net/the-26-an-hour-minimum-wage/↩

- [4]U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Federal poverty level (FPL),” n.d., https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/↩

- [5]Areeba Haider and Justin Schweitzer, “The Poverty Line Matters, But It Isn’t Capturing Everyone It Should,” Center for American Progress, March 5, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/poverty-line-matters-isnt-capturing-everyone/↩

- [6]David Benfell, “Reckless driving as routine,” Not Housebroken, January 28, 2023, https://disunitedstates.org/2023/01/25/reckless-driving-as-routine/↩

- [7]Laura Forman, “Lyft’s Defensive Driving Stalls Out,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/lyfts-defensive-driving-stalls-out-2efc5f99↩

- [8]Ashley Capoot, “Uber beats estimates and the stock is up,” CNBC, February 8, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/08/uber-earnings-q4-2022.html↩

- [9]David Benfell, “About my job hunt,” Not Housebroken, n.d., https://disunitedstates.org/about-my-job-hunt/↩